|

Bringing myself back to

the present, I realize that many things have changed here. Fish still

swim abundantly in this water, but the dark-skinned fisherman can

no longer be seen; nor can the child any longer be heard laughing.

All that remains of the Calusa are traces of daily life found in the

large shell mounds that exist on the shores of Southwest Florida.

Only pieces of their history have been painstakingly excavated from

the archaeological sites found on Pine Island, Mound Key, Estero Bay,

and Everglades National Park.

Researchers hope to learn

more about this extinct indigenous culture by studying the artifacts

they left behind. They hope to gain more of an understanding as to

what this culture, which was the predominant one long ago in this

part of Florida, can teach us about the present, especially about

environmental and ecological issues in this sensitive natural ecosystem.

Bits of shell and gravel crunch under

my feet as I walk along the entrance to the Randell Research Center.

Located at the Pineland Site Complex in Lee County, this research

and education program is operated by the Florida Museum of Natural

History. In 1996, Donald and Patricia Randell donated 53 acres of

land to the University of Florida, and the Research Center was created,

thus establishing a significant focal point for the study of the Calusa.

I approach the newly built visitors

center, anxious to meet Dr. John Worth, an archaeologist and ethno-historian

who coordinates the center's public-education programs and development.

After some initial introductions, we begin a journey on foot through

time along the Calusa Heritage Trail.

This 3700-foot interpretive walkway

leads visitors through the “shell mounds” — among

the most unique and intriguing archeological sites you will find anywhere

— along canals, and in and around numerous other surprising

features of this important Native-American site. Dr. Worth is a dedicated

researcher and scientist with extensive knowledge about the Calusa,

and a passion for telling their story. He explains to me that archaeology

is not an end result, but rather a long continuing process. He also

cautions me that despite our best efforts and best intentions, some

pieces of prehistory may remain hidden forever. I wonder if this is

a good or bad thing.

I am entranced with Dr. Worth’s

narrative abilities, especially his talent for bringing the Calusa

and their culture to life. Gradually I too begin to see them as real

people who were once completely and very successfully integrated into

this wetland ecosystem. Thanks to Dr. Worth, I no longer see the Calusa

as sad statistics from the past; in me he has found captive audience.

With little experience in such matters,

I begin to become aware that archaeology is not just a science of

the mind, but that it is also a science that relies heavily on intuition.

Archaeologists use their logic to decide when, where, why, and how

to dig but often, Dr. Worth tells me, they just have to go with their

gut feelings. And, as we discuss not only the Calusa but the art of

archeology, I discover that there are rarely easy answers to the mysteries

about ancient civilizations like the Calusa. I am also taken aback

when I learn that archaeology can be as disruptive as it can be enlightening.

Despite our different academic backgrounds,

Dr. Worth and I are both in agreement that there are many lessons

to learn about life — both ancient and contemporary —

and that many of these lessons lie just below the surface. And given

the very integrated and shallow wetland environment of this part of

Florida, there is much I learn about the Calusa just by examining

surface features. I forget the oppressive heat as Dr. Worth begins

to tell me the intricate story of the Calusa people and the land and

waters they inhabited.

The Calusa, or “fierce people”

inhabited the inner waterways of this area of Florida for about 1500

years until around the 1700s. They controlled most of southern Florida

under their leader Chief Carlos. Their population numbers may have

reached close to 50,000 when their civilization was at its height.

When Spanish explorers landed in this

area in the early 1500s, they described the Calusa as “fierce”

and “war-like,” and encountered heavy resistance. (I wonder

at the reasons why the Calusa resisted the arrival of the Spanish

and am reminded of the quote “Until lions have their historians,

tales of the hunt shall always glorify the hunter.”)

Juan Ponce de León is considered

to be the man who “discovered” Florida. He also died of

a wound from a Calusa arrow. Much of the information known about the

Calusa are from the writings of the explorer Hernando de Escalante

Fontaneda. In his memoirs, he wrote about his experiences, which included

contact with the Calusa when he was shipwrecked somewhere close to

the Florida Keys at the age of 13. Around 1549 he and his brother

were returning to Spain when they were shipwrecked in the area, possibly

as a result of a hurricane. The crew and passengers were rescued by

the Calusa who subsequently enslaved them. Eventually everyone except

Fontaneda was put to death. According to Fontaneda, his life was spared

because he was able to interpret their commands that he sing and dance

for them. He spent the next 17 years living among them and writing

about their way of life.

The Calusa lived and thrived near the

estuaries of the Caloosahatchee River, the “River of the Calusa,”

nearby what today is Ft. Myers. And it was this unique estuary ecosystem

that contributed to their very successful lifestyle which blended

with the natural elements.

An estuary is a dynamic and fertile

part of a river. As a freshwater river approaches the sea in its lower

course, the salty ocean water and the fresh water mix. It is a mixed,

somewhat contradictory, element but also a place of transition from

land to sea. Protected from the turbulent forces of the ocean environment,

estuaries are in-between aquatic places where unique and abundant

forms of life can thrive.

The estuary environment, along with

Florida’s subtropical coastal environment, provided an abundant

food source for the Calusa. In addition, it was a complex natural

environment in which the Calusa collected herbal medicines and materials

such as palm tree webbing to make nets. Relying entirely on this rich

environment, the Calusa also used spears and fish bone arrowheads

to catch turtles, eels, and deer. For many of us today, the area may

seem an inhospitable, often impenetrable, and exceedingly hot place

to live. But for the Calusa, the necessities of life were close at

hand. Although the primary work of the women consisted of caring for

the children and the home, it was they who caught the abundant shellfish

— crabs, clams, lobsters, oysters — along with the help

of the children. And the remains of their labors can still be seen

today.

The Calusa traveled in canoes made

of hollowed out cypress tree logs through an intricate system of canals

that they built using shells and sticks; an amazing engineering feat

for people who were living directly from their local environment over

1000 years ago — before human beings elsewhere had developed

stone tools. The climate afforded them the luxury of homes that had

no walls, and the roofs were made of palmetto leaves. Built along

the the canals they constructed, the houses were elevated on stilts,

only inches away from their food source. It is believed by some that

they traveled through the protected estuary network and as far as

Cuba. There were even reports that the Calusa attacked Spanish ships

anchored there.

The shell mounds that remain today

are actually piles of refuse; the natural materials the Calusa used

every day and then threw away. According to Dr. Worth, some of the

most revealing information about these people and how they lived comes

from these piles of refuse. Shells were central to their way of life;

from them they made tools, utensils, jewelry, shrines, and ornaments.

Environmentalist and conservation groups protect many of the shell

mounds that remain today because they are a rich source of information.

I find it fascinating that one of the principal activities of visitors

to places in the area such as Sanibel and Captiva Islands is spending

long lazy days collecting shells on the beaches.

Researchers believe that the Calusa

had a fairly complex society. Because of the abundance of resources,

they did not have to spend as much time hunting, gathering, or fishing

as many other native tribes elsewhere did. Their's was not a migratory

lifestyle; there was no need. And one can imagine how strongly they

must have identified with this environment and how protective they

must have been of it.

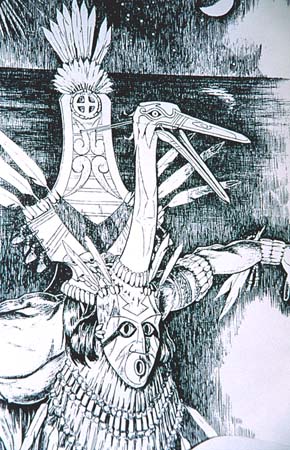

Being a far more “settled”

people than other indigenous people, they therefore had more time

to develop religious and political systems. The Calusa tribe was divided

into nobles and commoners (and possibly a slave class). There is some

suggestion that they even had an élite force of warriors. They

also had a king. Evidence indicates that they believed in an afterlife,

and had elaborate rituals which included daily offerings, processions

of religious leaders, synchronized singing, and even sacrificial worship.

The number three was a mystical number to them.

Like other native cultures, they had

a hereditary political organization; leaders were not elected, they

were born into their position. As proof of their high status, their

leaders also lived on the highest shell mounds. It was also a patrilineal

society; the eldest son inherited the power when the chief died. The

brother of the chief would become the shaman, or religious leader,

and the chief’s brother-in-law would become the warrior chief.

It was a “family business” that makes me think of other

contemporary political dynasties.

According to the beliefs of the Calusa,

each person had three souls: one was the shadow, one was the reflection,

and one was in the pupil of the eye. In their worldview, when a person

died the soul in the pupil of the eye remained, but the other two

moved into the bodies of animals. This cycle would continue; however

it was a negative chain of evolution. The latter two souls would transmigrate

from large to small animals. The soul was eternal, a continuing part

of nature — and of life.

Although all that Dr. Worth showed

me were really just traces of these people, I came to understand them

as real human beings who “once were.” They impressed me

as innovators in fishing and engineering, people that had faith in

their gods, their government, their people, and their natural home.

They were once like the rest of us. They laughed, loved, prayed, worked,

slept, and ate. They cared for their loved ones, survived harsh environmental

conditions, and continued to prosper for over 1000 years. They fought

for what they felt belonged to them: their land, their families, their

society, and their freedom. They fought and they lost. In the late

1700s, the Calusa people had almost completely disappeared because

of diseases brought by the Europeans, and fighting between the European

explorers as wellas that of rival tribes. A few Calusa escaped to

Cuba, and archeologists are still searching for possible descendants.

All of this left me to consider the

possibility of two truths in this story: that these people were truly

as fierce as the Europeans described them; or that that the Calusa

were protecting what they held most sacred. Perhaps they were who

they were and did what they needed to in order to protect what they

loved. Perhaps, like an estuary, the truth is somewhere in the middle.

It is certainly buried in the tomb-like shell mounds of Southwest

Florida.

As Dr. Worth explained to me, there

is much more to be discovered. However, the excavation of shell mounds

runs the risk of disrupting the very truth we want to uncover.

At the end of my time with Dr. Worth,

and my time among the Calusa, I ponder the mysteries of this extinct

people. Above me in the brilliant blue sky, a hawk cries. I look up.

I know the Calusa still have much to tell us. They too once thought

they would be here indefinitely. Perhaps their souls still are.

|

The

Calusa Indians:

Shell People of the Estuary

by Stephanie Moreland

The water

slaps the rocks on the shore of the estuary with a cadence that has

been heard by human beings for over 2000 years. In my imagination,

I hear the sounds of a child’s laughter, and see small dark

hands splashing in the water. In my mind’s eye, I see a tall,

bronze-skinned fisherman standing waist deep in the water. His long,

straight black hair hangs around the finely sculpted features of his

face. Creases form at the outer corners of his eyes and on his lips

from long days of working in the sun. His lean, muscular arms strain

under the weight of the net woven of palm leaves.

Lee County Visitor & Convention

Bureau

Lee County Visitor & Convention

Bureau

Lee County Visitor & Convention

Bureau

For

more information

The

Randell Research Center

The

Ft. Myers/Sanibel Convention and Visitors Bureau

Specific information about Calusa

history and genealogy:

The

Calusa

Indian History

Calusa-related attractions

The

Calusa Nature Center

and Planetarium

Museum

of the Islands

Calusa Indian Art

Calusa

Indian Art,

Artifacts, & Anecdotes

More on Lee County Florida

The

Bailey-Matthews Shell Museum

Lee

County Living

Unless

otherwise indicated, photographs by Stephanie Moreland |