|

|

They

Call It Rappie Pie: It’s been said that food is the most primal form of comfort. And I’m here to tell you that a dish called “rappie pie” is the ultimate comfort food in my books. But it bears no resemblance to what we normally think of as a “pie.” In fact, it is downright unappealing, visually. It looks like a blob of thick gray glue with small hunks of meat mixed in. Yet, mention rappie pie in certain parts of Nova Scotia and people’s eyes light up, their taste buds quicken, and they shiver with anticipation — including me! |

||

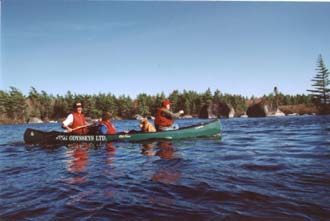

For rappie pie fans, the visual aspect is nothing to fuss about. It’s all about flavour, tradition, homecoming, family — and a good measure of Acadian pride in preserving this recipe. And furthermore, rappie pie is Nova Scotian soul food — rooted in the province’s Acadian culture. First, a little background. As far as I can determine, rappie pie doesn’t exist anywhere else in Canada except in parts of Southwest Nova Scotia, such as the Clare area, Yarmouth, Pubnico, and Wedgeport. In these regions, it’s a household name and featured in many restaurants. Yet, wander out of this geographic area (about a 40-mile radius) and you’ll be hard pressed to find anyone who’s ever heard of rappie pie. Although it’s unquestionably a French-Acadian dish, there are different views about its origin. Author Edith Tufts suggests that rappie pie was introduced to the Acadian communities after The Deportation in 1755 but prior to the Acadians returning. “Some were stranded in the Boston area where pretty little Acadian girls met up with some German soldiers stationed there. It was through them that they got this recipe for making what we call rappie pie — grated potato pie,” she says. After they returned to Nova Scotia, the Acadians grew lots of potato and it was a natural thing for them to adopt this new recipe. “It became un mets de rassemblement, a favourite dish popular for all sorts of gatherings.” Alain Muise, a well-known columnist, thinks that the history of rappie pie can probably be traced back to the Acadians who came to what is today Nova Scotia from Brittany or Normandy. There also could be a connection to the European potato pancake (latke) that’s now so popular in North America. Whatever its origin, rappie pie has been around our Acadian communities in Nova Scotia for many moons. It tops everyone’s list as the favoured dish for homecomings, christening, wakes, Christmas and New Years — just pick a time! I recently had some women friends over for lunch. Getting seven busy women together on the same day is no easy feat. But I mentioned that I was making a big batch of rappie pie and everyone showed up! So how is this weird and wonderful dish made, anyway? Traditionally, you’d start with a bucket of potatoes and grate them (using the small holes on a grater) then the grated potato would be wrung out in a cloth bag to remove liquid, leaving only the pulp. Today, companies do this commercially and the pulp can be bought in local grocery stores. One local company in Pubnico, D’Eon’s Bakery, uses the spin cycle on washing machines to extract the liquid. The next job is to cook a chicken in a big pot of water. Making a tasty broth is important, so add onions and liberal doses of salt and pepper. I learned from Alain Muise to also add a couple of chicken cubes, celery stalks, a chopped carrot and a little summer savoury. When the chicken is cooked, de-bone it and break up into small hunks. Strain the liquid and bring back to a boil. Now the fun begins. In a large bowl, slowly mix the hot broth into the potato pulp (five pounds of potato pulp will require about 20 cups of broth). Adjust salt and pepper. In a large greased pan (18x12x3 inches) pour half of the potato mixture, then arrange the cooked chicken on top along with three or four chopped onions. Cover with remaining potato mixture. Dot the top with small hunks of salted pork fat, or dabs of butter. Then cook in a 400-degree oven for three hours. The top should brown up and get nice and crispy. In the olden days, the Acadians often put duck, geese, rabbit, deer, pork — even clams in rappie pie. Some still do. It’s delicious any-which-way. Rappie pie is usually served with butter and can be accompanied by chow-chow, cranberry sauce or molasses. Some folks put ketchup on rappie pie but that’s surely a sin! Now, along with this mighty good Acadian dish comes something even better — Acadian life style and joie de vivre. I don’t know of any culture that has as much heart and soul. In my part of Nova Scotia, there are two distinct Acadian regions. Both are coastal. The bilingual folks who live here are descendants of the first European setters who came from France in the early 1600s. Each region is unique. Clare, for example, is on the west coast, situated on the Bay of Fundy. Clare is locally called the “French shore,” and spans a 35-mile stretch embracing over 50 villages and 10,000 people. It must be the longest main street in the world. It’s a happenin’ place that hums and buzzes with spirit. The Acadians here were originally farmers but when they resettled in Clare after the Deportation, the soil was poor and the landscape heavily forested. So they became fishermen, lumberjacks and woodworkers — skills in evidence today along thriving waterfronts, fish plants, lumberyards and shipyards. The churches in the region are also a testimony to the Acadians’ superb craftsmanship: to wit: Saint Mary’s Church, the tallest wooden church in North America, an engineering wonder designed by a person without any formal education. Further up the road is Saint Bernard Church, which was built from 8000 blocks of stone that were brought 120 miles by train. Two men then took the stones by ox-team from the station to the site. One layer of stone was laid every year from 1910 until 1942. Clare is also a hotbed of Acadian artists who work in a multitude of media including paintings, sculptures, pottery, quilts, stained glass, leather, wood, and photography. Many have studios and love to talk about their art and the Acadian lifestyle. If you are an outdoor enthusiast, you can golf, kayak, canoe, fish, swim, hike, go bird watching, beach combing, swim, or just tickle your toes in the sand at Mavilette Beach, my most favourite beach in the province. It’s simply stunning, and the sunsets in Clare are dramatic. So ask the locals to point you in the right direction. If you really want to get away from it all, I highly recommend Hinterland Adventures — an outfitting company led by Hantford Lewis, one of Canada’s top guides. My husband and I went wilderness canoeing with him in the Tobeatic Reserve — you can canoe there for three weeks and never see another soul. Imagine that! And for all you music lovers, be sure to ask for a schedule of Musique de la Baie, a unique program that takes place in local restaurants during lunch and supper. Various musicians take turns performing in different venues, providing two hours of Acadian culture and folklore through music and story. Bonus: it’s free with every meal! Chez Christophe’s is my personal favourite, as chef Paul serves not only rappie pie (and fricot, another popular Acadian dish) but also makes the ultimate fish cakes. Back on the road, head to West Pubnico, on the other side of Yarmouth. Drive through the community until you reach Le Village historique acadien de la Novelle-Ecosse (Historical Acadian Village of Nova Scotia). You’ll be greeted by the imposing hand hewn figure of Baron Philippe Mius d'Entremont, Pubnico’s founder. The site depicts what it was like in the olden days. The stories will make you laugh or give you goosebumps. You’ll learn how and why the early Acadian homes were insulated with straw, and all about the fish sheds that were built on the water’s edge — the precursor of multi-million dollar fishing plants. There are a number of vintage buildings and a handsome visitor’s centre. For history presented in a different way, drop into Le Musée acadien & archives. There’s always something going on in this fully furnished homestead built circa 1864, whether it’s a foot stompin’ kitchen party, a quilting bee, rug hooking, or a tour of the Acadian garden. You’ll also find an impressive camera collection, some awe-inspiring (and internationally famous) hand-carved duck decoys, a printing press and an excellent Research Center and Archives — great for genealogy buffs. This area is also famous for birding, especially for colonies of Roseate Terns and the museum hosts an annual three-day Tern Festival, which is drawing lots of attention. Before you head out of Pubnico, plan to drop into the Red Cap Restaurant for Helen LeBlanc’s seafood dishes and famous rappie pie. People drive for miles to eat here. It’s also a great place to meet local people and find out just how friendly and helpful they are. Don’t be shy to ask questions! Another famous Acadian community is Wedgeport. In the mighty tuna’s heyday, Wedgeport was recognized as the Sports Tuna Fishing Capital of the World. President Franklin Roosevelt, Amelia Earhart, Jean Béliveau, Ernest Hemingway, and many others boarded Cape Island boats and cast their rods here. From 1937 to 1972, Wedgeport also hosted the famous International Tuna Cup. The competition and camaraderie is legendary. Luckily, the stories live on at The Wedgeport Sport Tuna Fishing Museum and Interpretive Centre and the best news is that the Tuna tournament has been reinstated in August! The other treasure here is the Tusket Islands. Some say there are 364 — one for every day of the year. Many have intriguing names like Murder Island and Owl’s Head. The magic of the Tusket Islands is that it is a culture unto itself and it’s so rich in history. There are many shanties that still exist today. I especially appreciate the tranquility and the serenity of the islands. It’s really magical. Captain LeBlanc and his sons, Lucien and Simon give guided tours of the islands. You can get their contact information from the Tuna Museum (and their touring boat is docked at the wharf in front of the museum.) Bonus: the four-hour journey includes a feed of lobsters and mussels on Big Tusket Island, alias, St. Martin. It’s the best deal in Atlantic Canada — bar none. So there you have it — a touch of Acadian culture and cuisine. But watch out! The Acadian joie de vivre (and a taste for that crazy rappie pie) is catching. |

|||

Nova Scotia Tourism

Anna D'Alessio-Doucet

Ted D'Eon

Ted D'Eon

Photographs by Sandra Phinney unless otherwise indicated. The Story of the Acadians The story of the Acadian people is one of the skeletons in Canada's closet. They were, and still are, a culturally distinct French-speaking people who established the first permanent European settlement in North America, two years before Jamestown, Virginia, and 15 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. The Acadians, however, fell victim to “The Conquest” of Canada during which Britain wrested the colony from France. For many reasons, the Acadians, who lived on some of the best land in Canada's Maritime region, were considered a threat to the new English colony. They were therefore rounded up and deported from their homeland in 1755, primarily along the eastern seaboard and in particular to Louisiana. (Cajun is the word Acadien pronounced with an Acadian accent.) To read the full story

of the Acadian people, click

here.

To get an historical perspective on the Acadian people read The Legacy of Port Royal. To get a greater understanding of the Acadia-Louisiana connection read When's A Cajun and Acadian?

|

|||