|

Photo courtesy Le Moulin Inn & Spa

Mon

pays ce n'est pas un pays c'est l'hiver

Mon Pays begins with

a statement of belief that illustrates the universality of the relationship

with the wintry land which is deeply felt in Québec.

My country is not a country,

it is winter.

My garden is not a garden, it is the plain.

My road is not a road, it is snow.

My country is not a country, it is winter.

To people of both English and

French backgrounds, this song speaks to a profound part of the national

psyche. For Canadians from Atlantic to Pacific are internationally

renowned for their long, cold winters, and for their almost unique

ability to embrace them with resignation, if not actual delight.

But for the people of Québec,

winter and the many possibilities for enjoyment that it offers represent

an occasion for enthusiastic anticipation and eager participation

throughout the province from the moment the first snow falls to

the ground.

An Outaouais winter

This is particularly the case in l’Outaouais,

the part of Québec that sits right across from Ottawa and

includes the National Capital Region, Gatineau Park, and the charming

towns of Chelsea and Wakefield. It has many attractions to appeal

to visitors in every season of the year, but winter is an especially

pleasant time to spend here.

The range of activities, both outdoor and

indoor, is perhaps unmatched in any other area of the province.

It is possible to travel from the urban centre of Ottawa, with its

many historic sites, museums, and fine restaurants, into the wilds

of Gatineau Park within half an hour by car on the easily accessible

highway linking the capital to this magnificent nature preserve.

I recently spent a pleasant time exploring

this up-and-coming region of Québec as a guest of the local

tourist board, visiting for a short time in the fall and for a more

lengthy stay in January. Both times I was struck by the sheer variety

of attractions l’Outaouais has to offer, from cross-country

skiing to elegant dining, and from outdoor adventures to some of

the Canada’s most important museums and art galleries, not

to mention a world-class casino.

Getaway Outaouais

The winter season came late to eastern Canada

in 2007, and there was barely any snow on the ground when I boarded

the VIA Rail train at Toronto’s Union Station, on an early

January day, en route to Ottawa, the first stop on my Outaouais

adventure. Shortly after leaving the city, however, I was happy

to see the snow-covered fields glistening in the sun, and by the

time I arrived in Ottawa the clouds had moved in and it was snowing.

This was certainly a far more familiar winter scene welcoming me

than the one I had left behind in tropical Toronto!

The temperature had dropped considerably,

and I was glad that an already warmed-up Chrysler mini-cruiser was

waiting for me at the station, courtesy of the local tourist bureau.

As I left the national capital, and drove across the bridge spanning

the majestic Ottawa River, I caught a glimpse of the National Art

Gallery and the Museum of Civilization on either side of the river,

which separates the provinces of Ontario and Québec. After

dropping my guide off at the regional tourist office, I proceeded

north into Gatineau Park, ready for my first experience of a Canadian

winter so far this year. I was actually eager to catch up for the

winter activities I had so far missed in this current season.

A First Nations name

L’Outaouais is the Algonquin First

Nations word for the Ottawa River, and is used to refer to one of

Québec’s many tourist regions. Not as well known as

Montréal, Québec City, the Laurentians, or the Gaspé,

l’Outaouais has been eager to establish a position for itself

on the province’s tourist radar screen in recent years, by

highlighting some of its many appealing attractions, and in particular

their close proximity to each other.

Within minutes of leaving Ottawa and arriving

in Québec, I found myself taking the highway exit for the

lovely village of Chelsea, where I was to have lunch at a small

local eatery known as Café Soup’Herbe.

The name of this vegetarian establishment

is actually a French play on words, involving “soup,”

“herbs,” and “superb.” My lunch, a delicious

croissant sandwich of cheese, onions, and roasted red peppers, accompanied

by a fresh green salad, certainly lived up to the café’s

name billing. I was the only anglophone person in the restaurant,

and I enjoyed listening to my French-speaking fellow diners engaged

in friendly conversation over their lunch.

Bilingual Outaouais

Since my teens, I have travelled to various

parts of Québec many times, and have witnessed the dramatic

changes that have transformed its society beginning in the tumultuous

years of the “Quiet Revolution” of the 1960s. This was

the period when French-Canadians began to assert themselves in Québec

itself and on the national scene as a whole. In the half century

since then, the relationship between Québécois and

their fellow English-speaking citizenry has certainly had its ups

and downs, including two independence votes, the last one only narrowly

defeated in 1995. But for me, on every occasion when I visit Québec

I am always pleasantly reminded of my country’s bilingual,

bicultural nature, something that is easy to forget when one lives

in a multilingual city such as Toronto, where French is not as common

as some of the other languages that comprise Canada’s multicultural

reality.

In l’Outaouais, and Ottawa as well,

bilingualism is a fact of life. It is truly a border zone between

what High MacLennan the a famous Canadian novelist once called the

nation’s “two solitudes” of French and English,

where both are in close proximity to each other, and communicate

easily across the linguistic divide.

My guide José Lafleur, for example,

a charming young francophone woman and an Outaouais native, could

switch easily from French to English in conversations with me and

her colleagues. This is the case with many residents of the area,

on both sides of the border. There are sadly only a very few parts

of Canada where the national policy of official bilingualism appears

to be practised on an everyday level. I have had the pleasure of

visiting two of them, the province of New Brunswick and l’Outaouais.

I often wonder what it would take to plant this wonderful aspect

of the country’s cultural mosaic in other parts of Canada,

and reflect on how it would lead to greater mutual understanding

and appreciation among those who inhabit each of the “two

solitudes.”

The Outaouais sense

of adventure

But these musings were quickly dispelled

by what awaited me on my second stop that afternoon. This was Laflèche

Adventure, a huge outdoor activity centre that boasts the largest

natural caves in the Canadian Shield and North America’s longest

aerial park. The facility remains open year round, but attracts

most of its visitors during the summer months. Then they can soar

above the lake on a zip trek line, challenge themselves with an

obstacle course involving tarzan ropes, nets, and wooden trapeze-style

steps hanging from the trees, and hike nature paths through the

mountain slopes. Having exhausted their outdoor activities (and

possibly themselves as well!), visitors can literally go underground,

and explore the fascinating caves that water pressure has carved

out of the rock face over the millennia.

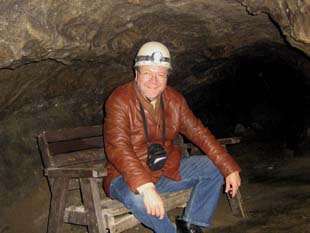

On the day I arrived, I was met by my guide

for the afternoon, Marc-André Dorval. Marc’s passion

is caves, and he is a well-known spelunker, or cave explorer. But

before we descended into the caverns, he urged me to at least attempt

one of the obstacle courses that remain open during the winter.

He showed me how to attach my harness to the zip line and encouraged

me to follow him in a dramatic swoop across the frozen lake, suspended

in space about 50 feet above ground. Unfortunately, I was recovering

from some recent eye surgery, and didn’t feel as bold as I

might usually have done. Instead, I was content to watch him disappear

along the zip line, only to resurface on the other side of the lake,

perched above a high wooden platform, waving at me. I did attempt

one obstacle course, climbing up to the top of the same platform

and stepping carefully along a series of wooden slats from tree

to tree. But the icy conditions of the course that day dissuaded

me from any further outdoor aerial adventures, and I was happy when

Marc suggested we proceed to our exploration of the caves.

Equipped with a miner’s hard hat with

a battery-powered light and a pair of high rubber boots, I was ready

to make the descent. While the caves are impressive at any time

of the year, perhaps they are at their most stunning in winter,

when icy stalactites and stalagmites appear to grow like mysterious

flowers from the cave ceiling and floor. For the first time I mastered

the difference between these two terms, which had frequently confused

me in the past. As Marc informed me, the French words tomber

(to fall) and monter (to rise) can serve as a useful aide-mémoire,

if one remembers that stalactites (with a T) descend from the top

of a cave, while stalagmites (with an M) rise from the ground.

We spent a few minutes in total darkness,

as Marc and I turned off our helmet lanterns to experience the complete

blackness of the cave. He told me that groups of young people sometimes

like to spend overnight trips in the caves, their sleep at times

disturbed by the flapping of the wings of the thousands of bats

inhabiting them.

|

Winter

Adventures in Québec's l’Outaouais

by Peter Flaherty

The legendary

Québec poet and chansonnier Gilles Vigneault is best

known for his song Mon Pays. This evocative hymn to Québec

culture has become the unofficial anthem of Canada’s predominantly

French-speaking province, which Canada's federal Parliament recently

recognized as “a nation within Canada.”

Last seven photos courtesy Tourisme

Outaouais

Outaouais Resources

Gilles

Vigneault's song Mon Pays

Tourism

Outaouais

Gatineau

Park

The

City of Gatineau

The

City of Ottawa

Chelsea

The

National Art Gallery of Canada

The

Museum of Civilization

The

War Museum of Canada

Laflèche

Adventure

Le

Moulin Inn & Spa / The Wakefield Inn

Le Nordik

Spa en Nature

L'Orée

du Bois

Le

Tartuffe

Guide

Debeur

VIA

Rail

|

We spent a few minutes in total darkness,

as Marc and I turned off our helmet lanterns to experience the complete

blackness of the cave. He told me that groups of young people sometimes

like to spend overnight trips in the caves, their sleep at times

disturbed by the flapping of the wings of the thousands of bats

inhabiting them.

For now, however, these nocturnal creatures

were all deep in their winter hibernation, their bodies suspended

on the cave walls, some of them completely encrusted with frost.

These bats are of many varieties, some of them with considerable

wingspans. I was not sure how I would have responded to them if

I were to spend a night inside these dark, narrow caverns.

Marc’s tour was extremely informative,

and he pointed out some of the recent explorations that experienced

spelunkers had been making, seeking to trace some of the tunnels

to their sources. He told me that many of these passages remained

unexplored, and that quite possibly the network of caves running

underground could be much more extensive than the considerable part

that had already been excavated.

Upon returning to the surface, I took a few

minutes to visit the gift shop, where some very attractive pieces

of jewelry made from polished stones were on sale. Marc talked with

me about the year-round operations of Laflèche Adventures,

and particularly of the young people who descend on the facility

every summer to find jobs as guides and facilitators.

An Outaouais inn

Somewhat tired from my explorations with

Marc, I was glad to return to my car and drive through the snow-covered

mountains into the lakeside town of Wakefield, one of the loveliest

spots in l’Outaouais.

My destination was Le Moulin, or the Wakefield

Mill Inn and Spa, the town’s premier lodging establishment

and my home for the next two pleasant nights. The inn is a lovingly

restored 1838 heritage stone mill, and my room faced the waterfall

that once powered the mill wheels for a grist, woolen, and saw mill.

Today it offers the visitor the comfort of 27 rooms, a fully-equipped

spa with outdoor jacuzzi, a charming bar with fireplace, and The

Penstock, a fine restaurant serving a variety of locally-influenced

dishes, based on French and Québécois cuisine. After

resting and taking in the stunning view from my window, I was ready

to enjoy a delicious diinner, accompanied by my host from the tourist

board.

From the elegant menu, we chose as our appetizer

a delicious pastry stuffed with goat cheese, accompanied by a sweet

fruit sauce. The main course was bison, raised on a nearby farm,

and cooked to perfection. Accompanying the meat was an excellent

red wine, which our waiter had carefully selected for us. Dessert

for me was the proverbial “no-brainer” when I visit

Québec. I am particularly partial to tarte au sucre,

a Québécois pie made with maple sugar and cream. I

have sampled this rich dessert many times in my travels across La

Belle Province, but I have to admit that the Penstock’s

version was one of the best I have ever tasted! Throughout our meal,

I enjoyed an animated conversation with Jose, switching from English

to French, over dessert, with my confidence in my linguistic abilities

perhaps fuelled by the glasses of wine I had sipped throughout dinner!

The next morning I awoke to a gray, rainy

scene outside, and wondered how the unpromising weather might affect

the winter activities in which I was expecting to participate that

day.

I had a delicious breakfast in the dining

room, joined by Robert Milling, the owner of the Mill, whose passion

for the building and its history was infectious. He described the

various incarnations of the property, from its days as the town’s

local mill through a disastrous fire that destroyed much of it early

in the 20th century to a period in which it remained practically

a ruin. The local tourist board planned to turn it into a working

museum of mill crafts, but the project soon proved to be beyond

its budget.

This is where Bob stepped in, with an ambitious

plan to restore the mill as an inn and spa. He showed me how local

stonemasons with 19th-century skills had to be be hired to reshape

the huge millstones on the first level, and how water damage from

an unexpectedly heavy spring run-off had almost sunk his project

in its early stages. But he was clearly proud of what he and his

wife had achieved, and was enjoying the fact that this property

was popular with individual visitors and corporate retreat groups

year-round.

A quiet Outaouais moment

After breakfast, Bob asked me if I was aware

of the fact that a famous Canadian Prime Minister, Lester B. Pearson,

was buried in the local cemetery perched on a hilltop above the

inn.I was vaguely aware of the fact,

but had never had the opportunity to visit the grave of this important

national figure.

Pearson had been the first Canadian to win

the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to dispatch UN

peacekeeping forces to the Middle East during the 1950s. Later,

as Prime Minister, his government had been influential in securing

the adoption of the red and white maple leaf flag as Canada’s

national emblem. Pearson died in 1972, and had asked to be buried

in Wakefield, in the middle of his beloved Gatineau Park. According

to Bob, one of Pearson’s sons still lives in the area.

The road from the inn to the cemetery was

difficult to travel on that day, because of the rain and slush,

but with Bob’s four-wheel drive vehicle we were quickly at

the top. As the mists covered the majestic hills, I stood at the

site of the grave of this major figure in Canada’s modern

history.

I reflected on the fact that unlike Americans,

who honour their former presidents extensively, we as a nation are

almost forgetful of those who have played such an important role

in shaping our national destiny. The maple leaf flag fluttering

over Pearson’s grave was a moving and appropriate reminder

of one of the significant contributions he and his government had

made to fostering Canadians’ sense of themselves as a proud,

independent country during the 1960s.

Leaving the inn, I drove down Provincial

Route 5 to my next stop, the main Visitor Centre of Gatineau Park.

There I was to meet with François Leduc, an extremely knowledgeable

member of the park staff who escorted me on a personal guided tour

of its many points of interest. Unfortunately conditions for cross-country

skiing were less than ideal on that day, with the rain turning the

snow already on the ground into a wet, slushy consistency. Nonetheless,

a few die-hard skiers were out on the trails making the best of

the situation. François informed me that on a normal winter

day the park would be very crowded, and many of the trails would

have quite heavy traffic. Later in the winter a number of ski weekends

and competitions were planned, and he was confident that conditions

would improve. And he was right — winter came late but with

a vengeance across southern Ontario and Québec a month later,

with major snowfalls and cold temperatures creating ideal cross-country

skiing opportunities in the Gatineau and throughout l’Outaouais.

Ah Gatineau!

There are very few major urban areas in North

America as fortunate as Ottawa to have such a treasure-trove of

natural wilderness so close to them.

Gatineau Park covers 363 square kilometres

of land, and permits visitors to enjoy a wide range of year-round

outdoor activities, including cross-country skiing and snowshoeing

in the winter, hiking and camping in the summer, and observing the

many species of birds, animals, and plants that flourish in its

environs. The Gatineau Hills were carved out of the landscape when

the glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age, over 10,000

years ago. About 5000 years later, the first native peoples arrived

to inhabit the area. Since then, explorers, fur traders, lumbermen,

colonists, and industrialists have all established themselves in

the region, taking advantage of its many opportunities for economic

advancement. Beginning in the early 20th century, the federal government

decided to create a park in the Gatineau, and in 1937 it acquired

the first 16,000 hectares of land, which has been continually expanded

since then.

One of the most famous historic sites on

the grounds of Gatineau Park is Moorside, once the summer home of

William Lyon Mackenzie King, who was prime minister of Canada during

the time of the Great Depression and World War II.

An eccentric, somewhat reclusive bachelor,

King loved the solitude of his home in the park, where he would

take long walks with his beloved dog Pat. Fascinated with ancient

Graeco-Roman ruins, King had a number of architectural specimens

brought to his home from European archeological sites, some delivered

across the Atlantic even during World War II! Inclined to mysticism

and believing it possible to commune with the spirits of the dead,

King loved to stroll the grounds of his estate at nightfall, absorbing

the aura of the ruins surrounding him.

When he died in 1950, he bequeathed his 231-hectare

estate to the Canadian people so that it would forever remain a

public park and nature sanctuary. In the early 1980s, the National

Capital Commission, the federal body responsible for administering

the area around Ottawa on both sides of the Ontario-Québec

border, restored the house and turned it into a museum. As a result,

it is now possible to obtain a first-hand look at how this mysterious

but important public figure in Canadian history conducted his private

life. There is a delightful café and teahouse on the site,

which is open from spring to fall.

Gatineau Park is home to over 1000 species

of plants and 50 types of trees. Approximately 230 bird species

have been observed there, including the pileated woodpecker, which

can be seen in winter. Fifteen of these species are on Québec

or national endangered species lists, including the loggerhead shrike

and the cerulean warbler. Fifty-four species of mammals make the

park their home, 14 of which are at risk in Québec or the

rest of Canada, including the timber wolf. About 2000 white-tailed

deer reside in the park, and there are also 2000 beavers and a few

black bears. The day I visited, François led me on a short

nature walk through the forest near the Visitor Centre, where we

saw a beaver busily at work building a dam on the river, and also

a woodpecker drilling into a tree.

We then went on a short drive through the

park, and François pointed out some of the major points of

interest. These included Camp Fortune, the only downhill ski facility

in the area, and Meech Lake, a popular summertime beach made famous

to Canadians for the abortive constitutional accord negotiated at

the federal government’s conference centre located there.

For enthusiasts of cross-country skiing,

Gatineau Park is a wonderland in winter. The park boasts almost

200 kilometres of trails, track set for classic skiing, of which

100 kilometres are also groomed for skate skiing. In addition, the

parkways, which are used as roads during the summer months, are

also converted into ski trails in winter.

The additional 30 kilometres of roads offer

spectacular scenery and excellent ski conditions for skiers of all

levels of proficiency, from beginners to experts. As someone who

enjoys cross-country skiing, I was somewhat disappointed that the

weather had not cooperated better in order for me to hit the trails

that day. But after seeing just how superb the facilities are in

Gatineau Park, I made a mental note to myself to return as soon

as possible to enjoy them.

An Outaouais spa

While my morning in the park may not have

been quite as strenuous as I had originally hoped, my lack of exertion

did not restrain me from taking full advantage of my next stop,

a luxurious new spa quite close to the park entrance called Le Nordik.

This brand-new facility attracts both local

residents and visitors to the area alike for its unique outdoor

ambience. Set on a wooded hillside, many of the attractions are

outside, including hot, cold, and temperate baths, and a waterfall

that descends right into one of the large jacuzzis. Inside it is

possible to enjoy a variety of massages, including Swedish, Californian,

Thai, and hot stone therapy. When I arrived, there were many people

making bookings for treatments, especially groups of women who were

there for manicures, pedicures, and other forms of female beautification.

Marketing and sales coordinator Kim Morrisette greeted me and gave

me an extensive tour of the spa before we sat down for lunch duirng

which I learned about the ambitious plans of the spa’s owners

to expand the facility. After lunch, she suggested I try the steam

bath and take the plunge into the cold pool right afterward!

A couple of turns in the hot steam room followed

by an extremely invigorating splash of cold water from one of the

waterfalls led me to the hot tub, where I relaxed in the open, marvelling

at the mildness of the outdoor temperature. After this I followed

the path to the large jacuzzi and the newly-designed waterfall,

landscaped right into the hillside. The hot streams of water that

descended on my body as I stood under the cascade created an extremely

pleasant sensation.

After this I entered the salon de détente,

or relaxation area, where I had planned to sit facing a picture

window, admiring the view, while reading the book I had brought

with me. Pouring myself a cup of warm herbal tea, I opened the book,

settled comfortably into my easy chair, and within a minute was

fast asleep! About a half-hour later I awoke feeling totally relaxed,

only to remember that it was time for my massage appointment. Will

this relaxation ever end, I wondered.

I entered the massage room and was greeted

by Marie-Claude, a pleasant young woman who was studying to become

a registered massage therapist. Her technique was very professional

and excellent, as she worked over whatever tense spots were left

in my neck and back after my pleasant afternoon at the spa.

After my session with Marie-Claude, I went

to the café, still clad in my cozy terrycloth bathrobe, and

enjoyed a glass of port while I contemplated just how completely

at ease I was feeling.

As the darkness settled in, I decided to

take one more plunge into the hot tub, where the lights and the

steam rising from the water created a mystical atmosphere.

A woodland restaurant

Leaving Le Nordik with some reluctance, I

was happy to know that dinner was awaiting me not far away, at l’Orée

du Bois one of the finest restaurants in the area.

Owned and operated since 1978 by the husband

and wife team of Guy and Manon Blain, this lovingly restored old

farmhouse set in the forest offers the visitor a wonderful selection

of French and Québécois cuisine. L’Orée

du Bois is a restaurant with close ties to the terroir,

or local area, and only serves dishes made from fresh produce purchased

from neighbourhood farms.

For example, Manon proudly showed me the

garden where the fresh herbs and vegetables are grown, and the smokehouse

where fish, poultry, and meat are smoked over a bed of sweet-smelling

maple sawdust. They even make their own chocolate on the premises!

The assistant chef, Jean-Claude Chartrand, is a graduate of a prestigious

French culinary institute, and has used his wine expertise to help

stock the restaurant’s cellar with a selection of fine vintages.

I started with a pâté de

fois gras fondant, the creamiest, richest pâté

I have ever tasted. As I savoured every mouthful, I sipped a cold

locally-produced apple cider, a wonderful drink to pair with this

hors d’oeuvre. This was followed by potage St. Germain,

a take on traditional French-Canadian pea soup that was truly filling

and delicious, especially when accompanied by home-made bread. As

a main course, I selected a confit de canard, a perfectly

cooked duck in a delightful sauce. I selected a fine Australian

Shiraz as my wine of choice that evening, and I was not disappointed.

Manon visited me frequently during the course

of my meal to find out if I was enjoying myself, even though the

restaurant was quite busy. She need not have worried in the slightest;

it was one of the finest meals I have ever eaten, anywhere! Still

finding room for dessert, I selected a terrine au chocolat,

a trio of different home-made chocolate creams which was much more

interesting than the usual mousse au chocolat found in many French

restaurants.

After sipping an excellent espresso, I was

invited to go into the kitchen, to give my compliments to the chef.

Guy was busy doing all the things chefs do in the kitchen —

tasting dishes, taking orders, and generally creating some sense

of order out of what appeared to me to be a scene of complete, if

creative chaos. But he was able to find a few minutes to talk with

me about my meal, and share some reminiscences of how he and Manon

had built their business over the years.

I later discovered that Guy and Manon had

been awarded the National Capital Commission’s Epicurean Award

of Excellence, a very prestigious culinary prize. The Guide Debeur,

the Québec equivalent of the Michelin guides, also recognizes

it as a four-star establishment. In my opinion, these acknowledgments

are completely deserved. L’Oree du Bois is one of those rare

establishments that combines food and service of superb quality

with a homey, unpretentious atmosphere that makes the visitor feel

quite comfortable, or chez nous (among us) as the Québecois

like to say.

Feeling lucky

I was feeling quite fortunate after my wonderful

meal at l’Orée du Bois, and since it was too early

to return to the inn, I decided to try my luck at the Casino du

Lac-Lamy, a modern gaming temple on the outskirts of Gatineau, a

short drive from Chelsea.

The building was glittering in the night,

and I hoped that lady luck might be beckoning me as I parked the

car and entered the huge hall. There are over 1800 slot machines

and 64 gaming tables at Lac-Lamy, along with a Keno room, Bingo,

and electronic horseracing. The casino boasts a fine restaurant,

Le Baccara.

In the Théâtre du Casino, a

state-of-the-art performance space, a number of famous performers

present a variety of different types of musical entertainment year-round.

Lac-Lamy is not just about gambling, and it can be a truly multi-faceted

experience for the visitor. However, on that particular evening

I was only interested in seeing if I could make the machines work

in my favour. Unfortunately, it was not to be, and a few dollars

poorer than when I entered the casino, I departed, reflecting on

the old truism, “the house always wins in the end.”

L'Outaouais is a mindful

experience

The Museum of Civilization

The final day of my Outaouais adventure was

spent in two of the area’s most renowned museums, the Museum

of Civilization in Gatineau and the newly opened War Museum across

the river in Ottawa itself . I had visited the Museum of Civilization

on my earlier trip to the area in the fall, when I toured the magnificent

Petra-Lost City of Stone exhibit, presenting the wonders of the

world-famous archaeological site of Petra in Jordan. I had had the

good fortune of being invited to Jordan in late summer 2006, and

had spent three memorable days at this incredible site, and my visit

to the Museum of Civilization’s exhibit was a delightful refresher

course in the wonders of Petra.

Some 2000 years ago, a mysterious Middle

Eastern people, the Nabataeans, carved out a city from the red stone

walls of a forbidding desert canyon in southern Jordan. For centuries,

Petra flourished as a major trading centre on the route from Arabia

to the Mediterranean, and the business-minded Nabataeans enriched

themselves from the traffic of desert caravans stopping there. The

city had an innovative system for supplying water, an amazing feat

considering the fact that Petra was built in the middle of a desert.

After the decline of the trade routes, Petra was abandoned and remained

a ghost city of legend for centuries until European archaeologists

rediscovered it in the 19th century. Today, it is one of the most

important sites in the Middle East, receiving large numbers of visitors

annually. It was made famous by the recent film Indiana Jones

and the Last Crusade, in which the façade of the Treasury,

Petra’s most famous building, is prominently featured.

The Petra exhibition at the Museum of Civilization

included more than 170 artifacts on loan from museums in Jordan,

Europe, and the United States, and was jointly organized by the

Cincinnati Art Museum and the American Museum of Natural History

in New York. It presented a fascinating portrayal of Petra and the

people who once lived in it, including stone sculptures and reliefs,

a wide variety of ceramic pieces, metalwork, inscriptions, and 19th-century

paintings of the site. Three remarkable examples of Nabataean artistry

were the sculptured frieze from a temple, a capital sculpted in

the form of an elephant head, and a huge bust of the god Dushara.

Large projection screens presented images of some of the more grandiose

buildings that can be seen in Petra, giving the visitor a virtual

experience of what the site is actually like. At some moments, I

actually had the uncanny feeling that I was back in Petra again.

On my second visit to the museum in January,

I returned to tour a recently opened exhibition entitled “Masters

of the Plains: Ancient Nomads of Russia and Canada.” My guide,

Elena Ponomarenko, originally from Russia, provided me with an extremely

informative guided tour of this exhibit, which highlights the striking

similarities in the ways of life of indigenous peoples of Canada

and the steppes of Siberia.

The First Nations peoples of the Canadian

prairies were bison hunters, while their Siberian counterparts were

livestock herders, but each group adapted to its very similar grassland

environment in remarkably parallel ways. The Canadian Museum of

Civilization and the Samara Regional Museum in Russia collaborated

in mounting this exhibition, which presented over 400 artifacts

drawn from both cultures. They illustrated various themes in the

lives of these two nomadic plains peoples, including food preparation,

sacred rituals and beliefs, forms of artistic expression, trade,

home designs and living space, means of transportation, and warfare.

The exhibit also focussed on the condition of these peoples today,

as the pressures of modern civilization have impacted on their traditional

nomadic lifestyles. I was especially fascinated with the recreations

of nomadic encampments, including a Siberian yurt and a Plains Indian

tipi.

A culinary interlude

Following my visit to the Museum of Civilization

I met José for lunch in a pleasant little eatery with a 1960s

theme, appropriately called “Le Twist.” It is a “resto

bar” with a retro feel, operating out of an old restored house

on the rue Montcalm, right in the middle of downtown Gatineau. On

offer are such traditional favourites as hamburgers, fries, mussels,

and a variety of salads. Québec is famous for its frites,

or French fries, and Le Twist did not disappoint. The burger was

thick and juicy, and for dessert Jose tempted me, with very little

protest on my part, to sample yet another tarte au sucre de

maison as a sweet farewell to l’Outaouais. We also sampled

one of the local beers available on site, a tangy brew with a reddish

colour.

The city of Gatineau has many fine dining

establishments from which the visitor can choose. On my previous

visit, I had enjoyed a delicious dinner at le Tartuffe, an elegant

restaurant within easy walking distance of the Museum of Civilization.

That night I enjoyed a terrine of game accompanied by a cranberry

sauce for my appetizer. In keeping with the game theme, I ordered

a succulent filet of venison for my main course, and followed it

with a delicious crème brûlé for dessert.

Chef Gerard Fischer made me feel quite welcome in his establishment,

surrounded by a group of business-style diners, many of whom appeared

to be government officials in the requisite suits and evening wear.

The National War Museum

The War Museum was my last stop on a winter

tour of l’Outaouais that had included a rich and fascinating

variety of outdoor and indoor activities, and I was glad that I

had saved this venue for last.

I had been anticipating a visit to the new

War Museum ever since it reopened in 2005, but until this time had

been unable to fit it into my travel schedule. As a former History

teacher, this museum had special meaning for me. I had toured its

predecessor, once housed in a cramped building in downtown Ottawa.

But this new facility, five minutes by car from the centre of town,

is a moving and completely fitting memorial to the wars Canada has

fought and those who have fought in them, from colonial times to

the present.

The award-winning architect Raymond Morayama

designed the building, and its glass roof and angled walls give

it an unforgettable appearance as one approaches it. Every year

on November 11, the sun shines directly though a slit cut in the

side of one wall, illuminating the Hall of Remembrance, the focal

point of the museum. A series of self-guided exhibits traces Canada’s

military history, from the early conflicts between English, French,

and Native peoples for possession of North America, through the

two world wars, up to the postwar period when Canada made its greatest

contribution to international peacekeeping.

Besides its permanent displays the museum

hosts a number of major temporary exhibitions, most recently “Afghanistan:

A Glimpse of War,” profiling Canada’s military mission

to that country, a point of contention and some controversy among

Canadians today.

I spent the entire afternoon visiting the

various parts of the museum, enthralled with the fascinating exhibits

of military hardware, contemporary films, propaganda posters, uniforms,

and televised first-person accounts of battles and campaigns.

In one gigantic hall known as the LeBreton

Gallery there is a collection of tanks, planes, military vehicles,

and artillery from both world wars and the postwar era. At one point

I was stunned when I came upon a white UN peacekeeping jeep that

had been shot full of bullet holes. My guide told me that a group

of Canadian soldiers had narrowly escaped death in this very vehicle

when they had come under hostile fire while on patrol in Croatia

during the early 1990s. I instantly recalled that one of those soldiers

had been a former student of mine, and how after he recovered from

his injuries he had revisited my classes to speak to students about

his experiences in war-torn Yugoslavia.

It is at moments such as this that history

seems to leap out of the museum pieces that preserve it, to remind

one of its living presence and direct impact on our lives. This

awareness was brought home even more forcefully when I visited the

Royal Canadian Legion Hall of Honour, which displays the heroism

of Canadians who fought in the major conflicts in which this country

has participated, past and present.

The War Museum is more than just a place

that stores and presents military artifacts and memorabilia. It

is a lively place where discussions, film events, and other public

gatherings are hosted, often with major military and academic figures

in attendance. School groups are welcome, and I left wishing that

the museum had been completed while I was still teaching Canadian

history to my students. It would have made a wonderful field trip

to the national capital, where they might have obtained a privileged

look at the record of Canada’s fighting men and women throughout

history, something much more powerful than any textbook account

could provide.

Au revoir but

not adieu

It was after five o'clock in the afternoon,

and the War Museum was closing for the day as I waited for the taxi

to take me to the Ottawa VIA Rail Station for my return train trip

to Toronto.

I had spent a fascinating winter interlude

in l’Outaouais, enjoying a wide range of activities both indoors

and out, and came away with a sense of anticipation for all the

things I wanted to do there on my next visit. The official motto

of the tourist board says L’Outaouais — vivez-le!

(The Outaouais — Live it!).

I realize that I did exactly that.

|